Patients refusing to use personal protective equipment, like masks, defined as “threats.”

Portuguese health authorities conducted a formal avian influenza (H5N1) simulation exercise in early 2025 to test how primary health care units would respond to a bird flu outbreak, according to a study published last week in Acta Médica Portuguesa and indexed by the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

The exercise comes as bird flu is simultaneously being advanced through expanded PCR surveillance, laboratory-engineered H5N1 research, and revived mRNA vaccine programs, raising questions given the similar convergence of testing, research, and preparedness measures that preceded COVID-19.

The exercise took place on February 3, 2025, and was coordinated by the Infection Prevention and Control Programme responsible for primary health care units in Northern Lisbon, within the Santa Maria Local Health Unit.

According to the authors, the event was a tabletop exercise—a structured simulation used to rehearse decision-making during hypothetical outbreaks—designed to assess whether frontline clinics could identify, isolate, and manage patients during high-risk infectious disease scenarios.

What Was Simulated

The exercise explicitly included avian influenza A (H5N1) as one of its outbreak scenarios, alongside Marburg virus disease and measles.

Participants were initially presented with blinded clinical and epidemiological information and asked to respond without knowing the pathogen in advance.

The diagnoses—including H5N1—were disclosed only after discussion.

Who Participated

Representatives from 15 primary health care units, accounting for 83% of clinics in the region, took part in the exercise.

Participants included healthcare professionals and unit leadership responsible for infection control and patient flow.

What the Exercise Tested

The simulation evaluated:

- Early identification of suspected infectious cases

- Availability of isolation rooms and isolation pathways

- Staff familiarity with mandatory reporting and isolation procedures

- Communication between clinics and external health authorities

- Barriers to compliance, including “uncooperative” patients and language obstacles.

‘Uncooperative’ Patients as a Defined ‘Threat’

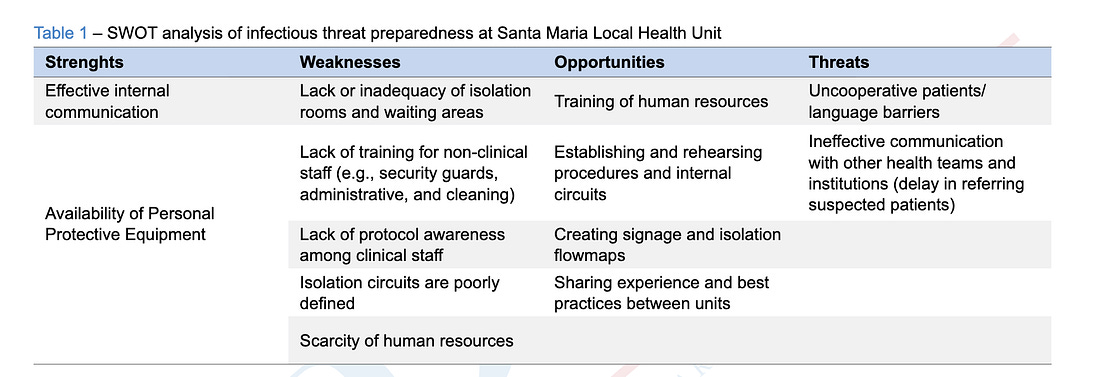

The authors explicitly frame patient non-compliance as a threat to outbreak control during the simulation, rather than as a secondary or peripheral challenge.

They write:

“[L]anguage barriers or non-cooperative patients (e.g., refusing to use personal protective equipment) were seen as threats to implement procedures correctly.”

In the study’s structure, this language also appears under the “Threats” category of the SWOT analysis—placing patient behavior alongside infrastructure failures and staffing shortages as factors that could actively undermine outbreak response.

The paper also notes that frontline clinics lacked personnel trained to manage or redirect patients once non-compliance occurred:

“[C]oncerns were raised about non-healthcare professionals in several units, such as security guards and administrative assistants, lacking training to identify potential infectious diseases and guide patients towards isolation circuits and/or alert healthcare workers.”

This framing treats refusal—specifically refusal to use personal protective equipment—as an anticipated operational risk during an infectious disease response scenario.

The authors do not describe voluntary refusal as a matter of patient autonomy.

Instead, refusal is listed as an obstacle to the correct implementation of procedures, implying a need for enforcement capacity that clinics were found to lack.

No mitigation strategies for patient refusal are proposed in the paper.

No limits on enforcement authority are discussed.

The simulation record shows that non-cooperation was expected, identified in advance, and formally categorized as a threat within a modeled H5N1 outbreak response.

Why This Exercise Draws Attention

Although the simulation occurred in early 2025, the study was submitted in July 2025, accepted in December, and published online January 8, 2026, placing it into the medical literature at a time when international concern over bird flu preparedness is intensifying.

The timing and structure of the exercise are notable.

In the years preceding COVID-19, global health institutions conducted high-level pandemic simulations—including SPARS Pandemic 2025–2028 and Event 201—that modeled coronavirus outbreaks, public messaging challenges, and emergency countermeasures shortly before those scenarios became reality.

This Lisbon exercise follows the same pattern:

- a named pathogen,

- a simulated outbreak,

- documented preparedness gaps,

- and publication after the fact to formalize the response framework.

The study documents preparedness planning.

It confirms that bird flu is now being actively rehearsed as a plausible next pandemic scenario, not only in abstract policy discussions, but through operational simulations involving frontline civilian healthcare systems.

Was the exercise solely for preparedness, or does it function as early-stage coordination for future response architectures?

Leave a comment